The Dada Movement

Paris

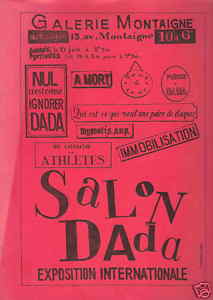

Dada movement letterhead

Salon Dada. Poster, Paris, Montaigne Gallery, June 3-6-30 1921. The international exhibition organized by Tzara under the name of "Salon Dada" in the hall of the Montaigne Gallery, just above the Champs-Élysées theatre, assembled a medley of a hundred incongruous works submitted by about twenty French and foreign artists.

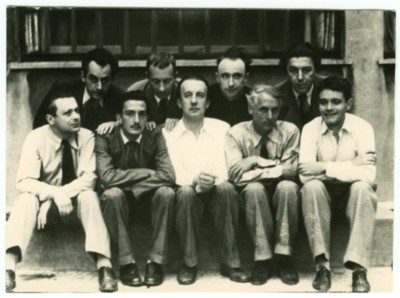

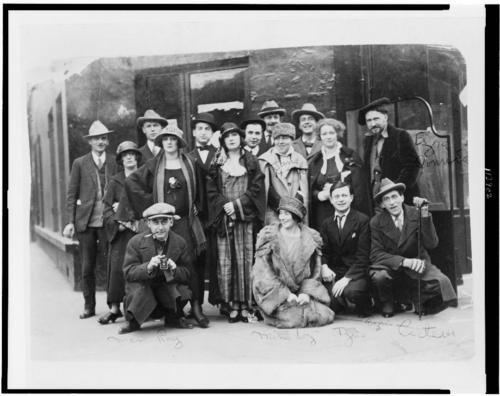

Back row: Man Ray, Jean Arp, Yves Tanguy and André Breton.

Front row: Tristan Tzara, Salvador Dalí, Paul Éluard, Max Ernst and Rene Crevel.

(Photo Man Ray, 1930.)

The study of Parisian Dada is of limited interest to the art historian, for the French capital was predominantly the scene of an ideological or literary battleground. Actually, Dada produced only two French artists of major importance -- Duchamp and Picabia.

Out of the junction between on the one hand, Picabia and Tzara, who had arrived in Paris from Zurich respectively in 1919 and 1920, and on the other hand the group

André Breton,

Louis Aragon,

Philippe Soupault,

Paul Éluard

formed around the little periodical Littérature, was born the French branch of the movement, the most notorious because it was to serve somewhat as a sounding board to Zurich dadaism. Its brilliant Parisian career, opened with a flourish in January 1920, was to end in a slump four years later. Meanwhile it had sponsored a great number of manifestations, exhibitions, shows, public provocations, a burst of manifestos, pamphlets, magazines and books, sometimes extremely varied, but always bearing Dada's iconclastic and irreverential hallmark.

Louis Aragon and André Breton in 1924

Opening of the Max Ernst exhibition at the gallery Au Sans Pareil, May 2, 1921.

From left to right: René Hilsum, Benjamin Péret, Serge Charchoune, Philippe Soupault on top of the ladder with a bicycle under his arm, Jacques Rigaut (upside down), André Breton and Simone Kahn.

However, the united face the Dadaists showed the public was already cracked. Only a few weeks after its formation, the group split up into two factions: a Zurich radical wing, led by Tzara; and a Parisian tendency, represented by Breton and his friends who, more open to the literary tradition, was to resurface in 1924 under the new name of surrealism.

This hyperactive current surged on, from one country to another, all the way to the antipodes. About a hundred artists claimed to be inspired by Dada and produced highly varied works under its influence.

Dada soirée, Salle Gaveau, Paris, May 26, 1920 (from: Hans Richter, Dada - Kunst und Antikunst, Dumont, 1964)

At the beginning, Dada borrowed elements from various pre-war "modernist" schools (futurism, cubism, expressionnism, etc.). But it exploited its predecessors' techniques to diametrically opposite purposes through a subtle process of "denaturation". In this way, for example, the typographical dismembering brought into fashion by the futurists in their Parole in Libertà would reappear systematically in the Dada tracts and pamphlets of Zurich, Paris and Berlin so as to become the undisputable trademark of the movement. It was no longer any question of pulling a new kind of beauty out of a jumble of type fonts, but rather of showing the vanity of all esthetic effort. Along the same lines, always following in the futurists' lead, Dada would make much of the machine. But where Severini and Balla were its high priests, Ernst, Duchamp and Picabia aspired only to desacralize it by replacing it in a perfectly unlyrical context (Duchamp's Broyeuse de chocolat). No more than man himself, the machine, his "daughter born without a mother," finds no favour in Dada's eyes: it is happily torn apart, raped, mocked, parodied. We find countless examples in Picabia's work of disparate mechanical elements distributed in haphazard order, as in Petite solitude au milieu des soleils, a machine that could never function and was therefore condemned to sterility.

Dada Group around 1922, 13,7 x 26 cm. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (acquired in 1987). From left to right, back row: Paul Chadourne, Tristan Tzara, Philippe Soupault, Serge Charchoune. Front row: Man Ray, Paul Éluard, Jacques Rigaut, Mme Soupault, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes.

(Photo Man Ray)

Dada group in 1921.

(Photo Man Ray)

The usual suspects: Front row: Tristan Tzara, Andre Breton, Salvador Dali, Max Ernst,

Man Ray. Back row: Paul Eluard, Hans Arp, Yves Tanguy, Rene Crevel in 1933.

(Photo Man Ray)

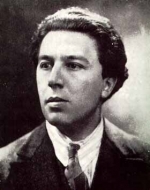

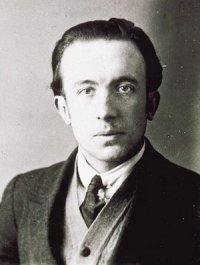

Louis Aragon 1897 - 1982

Louis Aragon 1897 - 1982

A major figure in the avant-garde movements that shaped French literary and visual culture in the 20th century, Louis Marie Alfred Antoine Aragon was born in the Beaux Quartiers arrondissement of Paris in 1897. His parents were unmarried, and Aragon grew up believing his mother was his sister, his father his guardian, and his grandmother his foster mother. A precocious student, Aragon completed his first novel as a young boy and later studied at the Lycée Carnot in Paris, where he earned degrees in Latin and philosophy. In 1917, he enrolled in the Faculté de Médecine de Paris and met André Breton. Aragon's writing also came to the attention of Guillaume Apollinaire during this time. Aragon was drafted into World War I, eventually earning a medal for bravery, and soon began writing poems. In 1919, Breton and Aragon edited the first issue of Littérature with fellow poet Philippe Soupault, giving birth to the Paris-based version of Dada. Aragon staged Dada events throughout the 1920s, publishing collections of poetry such as Feu de joie (1920) that reflected a Dadaesque interest in the absurd. He also began publishing novels such as Anicet ou le panorama (1921) and Les Aventures de Télémaque (1922).

By the mid-1920s, Aragon and Breton had turned their attention to surrealism. Aragon's Le Mouvement perpétuel, poèmes (1920–1924) (Perpetual Motion: Poems [1920–1924]) was a manifesto and poetics of the new movement. In the work Le Con d'Irène (1928), Aragon spoke to the influence of automatic writing: "What I am thinking naturally expresses itself. Everyone's language differs each from each. I for example do not think without writing, which is to say that writing is my method of thinking." In 1928, Aragon also met Elsa Triolet, the sister-in-law of Vladimir Mayakovsky. Aragon and Triolet fell in love and remained committed to one another - —and increasingly, radical politics - —for the rest of their lives. Triolet's commitment to communism strengthened Aragon's, and he began his series Le Monde réel, a surrealist political work that uses social realism to attack bourgeois literary and cultural norms. The books that comprise the series are frequently seen as forerunners of the nouveau roman movement in French literature of the 1960s. Aragon was drafted into World War II and again won commendation for his bravery, including leading a daring escape of 30 men from German forces. Demobilized by 1940, Aragon worked for the resistance, writing pamphlets, editorials, and poetry.

After the war, Aragon wrote a number of nonfictional studies, monographs, translations, and books on history, politics, art, and culture. In all, he would publish more than 100 books during his lifetime, as well as several posthumous volumes. He was one of the most important writers in post-war France, and his spirit as well as his writing did much to shape the intellectual landscape. He continued to write prolifically until his death in 1982.

Christian

Dada writer and artist Christian (born Georges Herbiet, Antwerp 1895 - Paris 1969). Close to Picabia, Jean Crotti and Suzanne Duchamp, Christian was intimately involved in the publication of a number of Dada reviews, contributing to 391 and Le Pilhaou-Thibaou, as well as to Action, L'esprit nouveau and the special dada issue of Ca ira; in 1922, he also published the sole issue of Picabia's La pomme de pins and Pierre de Massot's De Mallarmé à 391 (for which he wrote the preface) from Saint-Raphaël in the south of France, where he had moved in 1920, opening a bookstore.

"Vers 1923, il travaille à un "Traité d'harmonie," un système d'esthétique globale à visée scientifique, dont il reste des études sous formes de diagrammes. Il s'essaie également à la peinture figurative; quelques-unes de ses toiles sont publiées par The Little Review en 1922. Mais l'oeuvre de Christian est rare, l'artiste ayant été peu productif." (Nathalie Ernoult).

Ars Libri, Ltd.

Arthur Cravan

Arthur Cravan was - as he never tired of telling people -- the nephew of Oscar Wilde. A self-declared citizen of twenty countries, he was a dandy, forger, flaneur, critic, sailor, prospector, card sharp, thief, editor and chauffeur. He was the true father of dada and surrealism whose real work of art was himself.

Between 1911 and 1915, Cravan wrote and published the magazine Maintenant in Paris, which he filled with belligerent diatribes and scandalous braggadocio. He gave lectures, during which he insulted, mooned and fired guns at the audience. As an act of artistic bravado, he fought the heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson, and was knocked out as soon as Johnson tired of the charade.

On the run from the First World War, Cravan set sail from Mexico in 1918, intending to reach South America. He was never seen again. But no one knows what happened to him and no body was ever found. But poems and paintings attributed to Cravan continued to surface. And who exactly was the person identified as Arthur Cravan spotted in different parts of the world for decades?

Arthur Smith is beguiled by Cravan's sense of provocation, by his desire to live a rich and full life, a poetic life, in spite of it all. And in this program he'll call the final meeting of the Arthur Cravan Memorial Society to order as he tries to cobble together the truth about this mysterious and fascinating figure.

Listen to the BBC radio program on Arthur Cravan aired March 19, 2013 on BBC4 in London.

Producer: Martin Williams.

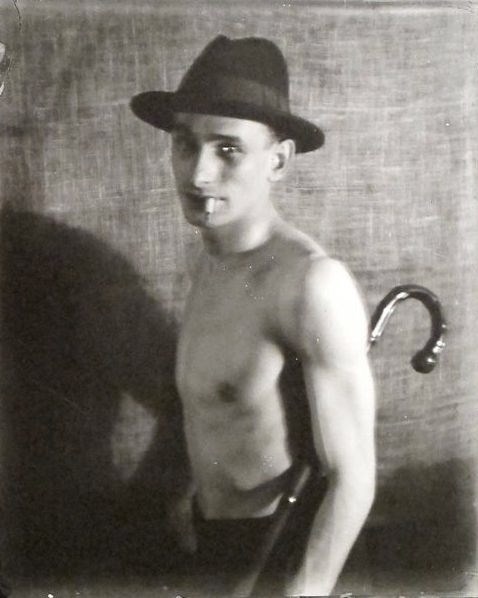

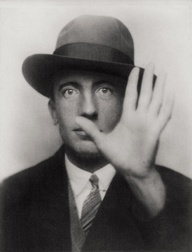

René Crevel 1900 - 1935

Portrait par Man Ray - 1925

Article in Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

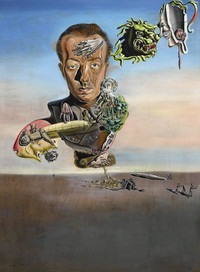

Paul Éluard 1895 - 1952

Éluard, who was a close friend of André Breton, took part in all the dada manifestations. He published Proverbe in which he appeared to be obsessed by the problems of language, like Jean Paulhan.

Portrait de Paul Éluard by Salvador Dali (1904 - 1989)

Oil on board

33 x 25 cm. - 13 x 9 7/8 in.

Painted in 1929

Estimated Price: 3,500,000-5,000,000 pounds

Selling Price: 13,481,250 pounds

Proverbe

Paul Eluard (14/12/1895 - 26/11/1952) - Poetic Evidence

Paul Eluard was the pseudonym of 'Eugene Grindel' a French poet who was one of the founders of the Surrealist movement. Initially connected to the Dada movement, he drifted away after a split that had divided it into two different philosophies, that of Anarchism and Communism.

Just after the First World War he became acquainted with three other Surrealist poets; Andre Breton, Phillipe Soupault and Louis Aragon, as well as becomming friends with the Surrealist Painter Max Ernst. He was to have a long association with them until around 1938. Experimenting with rythym, automatic writing, dreams and reality, and new verbal techniques soon became an everyday motion, and the poems that he created in this time are considered to be among the best that emerged out of the Surrealist movement.

After losing his first wife Gala, a mysterious and intuitive women to first Max Ernst, then subsequently to Salvador Dali, he spent a long time bereft in losing her love, however in 1934 he remarried Maria Benz (Nusch), an actress and model who was friends of Man Ray and Picasso.

After the Spanish Civil War which deeply affected him, he abandoned his Surrealist experimentations and in 1942 joined the Communist Party, and his work from now on reflected his growing militancy, and his rejection of tyranny, dealing with the sufferings and brotherhood of man,and the political and social ideasof the previous century. He began to regard poetry as a means towards radical change. During the Second World War he wrote verse that inspired and raised the morale of members of the French Resistance Movement.

After the war he continued to write on themes of Peace, self government and liberty. He married again to a Dominique Laure in 1951, who he had met at the Congress of Pea, Mexico, 1949. Sadly a year later he died of a heart attack in Paris. His legacy is found in the beauty of his words, his voyage through great moments in history, his life of tumultuous emotion and passionate imagination. His later work manifests the delicacy that was apparent even in his most political poems of the war years.

more

teifidancer - 14 April 2013

photo par Man Ray (1922)

Jacques Vaché

Jacques Vaché age 19

Jacques Vaché adult

Wikipédia

by Jill London - May 11, 2013

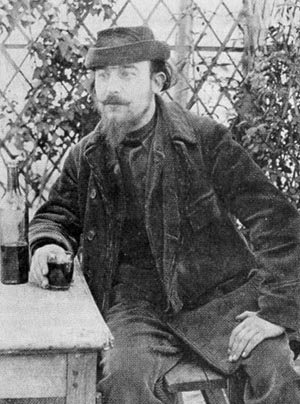

Who is the velvet gentleman? It is said that the velvet gentleman only ever ate white foods. It is said that of his 27 years in residence at Arcueil, France, not one of his friends were ever invited inside and that after his death 84 identical handkerchiefs and dozens of umbrellas (numbered sometimes at 100 or 200) were discovered in his one bedroomed apartment. He kept a filing cabinet filled with drawings of imaginary buildings which he would sometimes post about in anonymous advertisements to local journals:

"A castle in lead, for sale or rent."

He started his own religion, of which he was the only member, and wore a priest-like habit until he adopted the grey velvet suit as his public image, along with the bowler hat and umbrella of the bourgeoisie (though his politics ranged from socialist to communist). He worked with Man Ray and Francis Picabia yet is not considered a surrealist. It is difficult to sum up such an unconventional and bohemian a character as much of what he said and wrote acted as a kind of barrier between himself and the outside world. We can rarely take his words at face value but instead must sift and sort and read between the lines, and yet, I think if you try this tactic you are in danger of losing the man entirely.

more

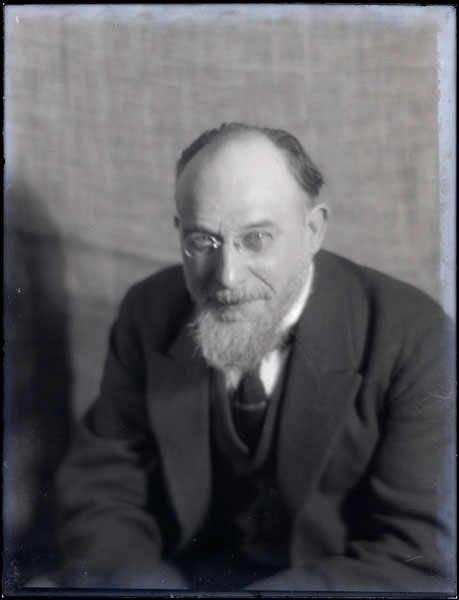

Erik Satie, the Dada-Dandy: Public-Private Partnership

Erik Satie emerged every morning from his tiny rented room in Arcueil, on the outskirts of Paris, dressed exquisitely in a velvet suit of which he owned an identical dozen, bought in the early 1890s with an inheritance. His dapper appearance was matched in his correspondence, –even the most trivial note written in flawless copperplate, and in his painstaking music notation.

When, after his death, Satie's room was entered by his brother and small group of friends, including the composer Darius Milhaud, no-one but Satie had entered the room for more than twenty years – not even the 'large and splendid concierge'. Milhaud recalled "what a shock we had on opening the door!" The room inside was horrific: "an unbelievable slum, an unforgettable rubbish heap". There was hoarded newspaper, unopened parcels, dust, grease and – according to Robert Caby "numerous lumps of excrement, hardened and blackened with age, which I hastily stuffed into newspapers so that Satie's brother shouldn't see them."

This is where biographical information becomes troublesome. The velvet suit, the exquisite handwriting - these seem to fit with the music. The filthy room, unopened piano, dust and excrement - does not. But that is the room, whether we like it or not, in which Satie wrote Parade, Relâche, Socrate, and from which he emerged every day looking 'rather like a model civil servant'.

Satie's gift was more modest than he was, particularly when compared with contemporaries like Fauré and Debussy. Jane Austen described her talent as "the little bit (two inches wide) of ivory on which I work with so fine a brush as produces little effect after much labour", and could apply equally to Satie. He had a restricted range, but one uniquely his. And amongst the ivory-polishers are many important composers: Chopin, Webern, Reich, Nancarrow. Even Stravinsky, the towering genius of twentieth century music, overcame his deficiencies as melodist by stealing tunes and bringing rhythm to the forefront.

Satie's music has the same aloof exterior and unknown interior as Satie the man. Who can say what led him into the lifestyle he adopted, or what his state of mind was. But I see Satie as a heroic, not a tragic, figure. Like Oscar Wilde, his genius was in his life as much as his art. He would don character of the boastful, irascible composer as he donned his velvet suit in the morning, before spending his days touring the bars of Paris. The poverty of his bedroom was irrelevant to his public life as the view of the unpainted back of a stage set from the wings is to the theatre-goer.

Those who entered Satie's room after his death felt as if they had 'penetrated his brain', but if you dissect a dead brain it does not give many clues to the character of the person when alive. Did Satie's lifestyle shape his music, or the other way round? Who knows. Certainly both are obsessive, eccentric, perplexing, but looking for meaning is probably the surest way not to find it.

Satie died at the age of 59 in a nursing home, of cirrhosis of the liver, having spent his last few days drinking champaqne and rejecting visitors as his strength gradually diminished. His last words were 'Ah! The cows...' (Ah ! les vaches... = Ah ! les salauds...)

by "The Earwig"

Erik Satie's "Vexations" (1893 to 2010)

Played during Nuit Blanche by Martin Arnold - and Micah Lexier - Toronto, Canada

Two Pianos, Table, 840 sheets of paper (folded)

This year Nuit Blanche began in Toronto at sunset on 2 October 2010 and continued through the night to dawn on 3 October. There were art exhibits, installations, and events open all over downtown.

Written in 1893, Erik Satie's "Vexations" was never published nor publicly heard during his lifetime. He left 39 beats of hand scrawled, insidiously vexing music—, hard to read and hard to remember— and the following cryptic instruction: "To repeat 840 times this motif, it is advisable to prepare oneself in the most absolute silence, by some serious immobilities." A number of performers (most notably John Cage) have ventured to take him at his word and successively play the piece 840 times, taking between 15 and 27 hours to do so. We only have 12 hours so we're dividing it: two pianos playing simultaneously, 420 passes per piano. Our "Vexations" is staged in the majestic arched expanse of a cathedral of commerce, perhaps therefore taking part in a highly irregular sort of exchange. We'll be counting tonight, by playing 840 scores each a vexation— once. After each score is played it is transformed into a folded paper sculpture, 840 scores creating 840 objects —giving shape to the sound and echoing the team of pianists weaving the composition's unmonumental but resolutely vexing notes. Satie said: "Before I compose a piece, I walk around it several times, accompanied by myself." We invite you to walk around "Vexations", hopefully several times as it accumulates through the night.

Martin Arnold and Micah Lexier are both based in Toronto. Arnold's compositions are performed nationally and internationally. Lexier is a visual artist, a collector, and (sometimes) a curator. Arnold is active in Toronto's improvisation and experimental jazz/roots/rock communities performing on live electronics, banjo, melodica, and hurdy-gurdy. Lexier has a deep interest in measurement, numbers and the kinds of marks we make in our day-to-day lives. Arnold teaches at Trent University. Together their ages equal 99 years.

Erik Satie by Man Ray

Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes 1884 - 1974

Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes 1884 - 1974

In Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes's machine pictures, painted gears, shafts, and wires create obscure contraptions suggesting that the forces of production have run amok. The words included compound the enigma: the phrases "liquid love" and "surface of soluble hopes" appear on Oceanic Spirit. The name of a Hungarian city, "Szegedin" appears on Silence. Ribemont-Dessaignes's sensational performances at a number of Paris Dada events revealed his combative side: he hurled insults at the audience, promising to "rip out your spoiled teeth, your pummeled ears, your tongue full of sores."

Ribemont-Dessaignes - Silence. c. 1915. Oil on canvas