The Dada movementMarcel Duchamp

|

The Dada Movement - Berlin, Cologne, Hanover, HollandDeutschland Dada: An Alphabet of German DadaismParts 1 & 2 - 1969Helmut Herbst - Director, Cinematographer, Screenwriter This superb documentary concerns the contributions of German artists to the Dada movement. Created in 1916, the organizers rejected previous convention and delighted in nihilistic satire in painting, sculpture and literature. Comparisons are made between the movement and the political and social upheaval at the time of the release of this feature (1969). Dan Pavlides, All Movie Guide |

|

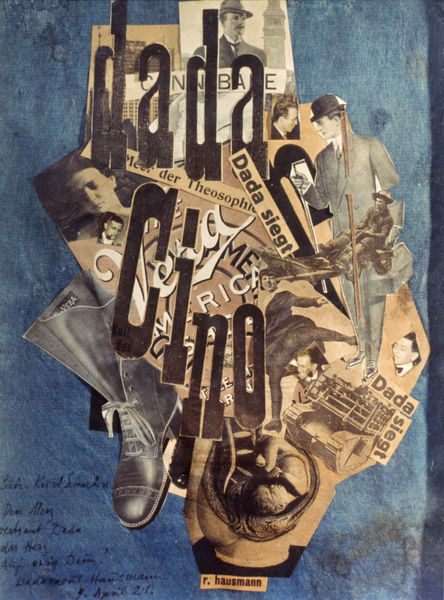

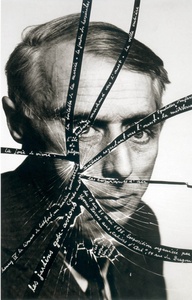

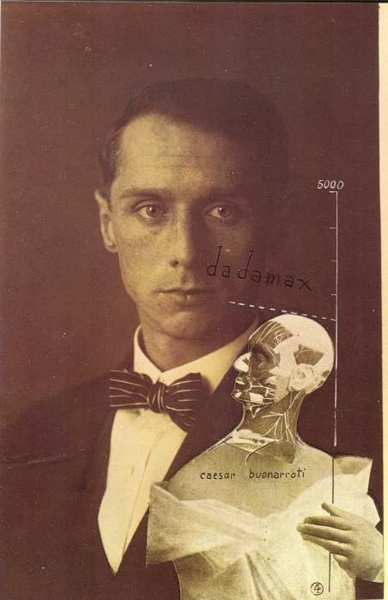

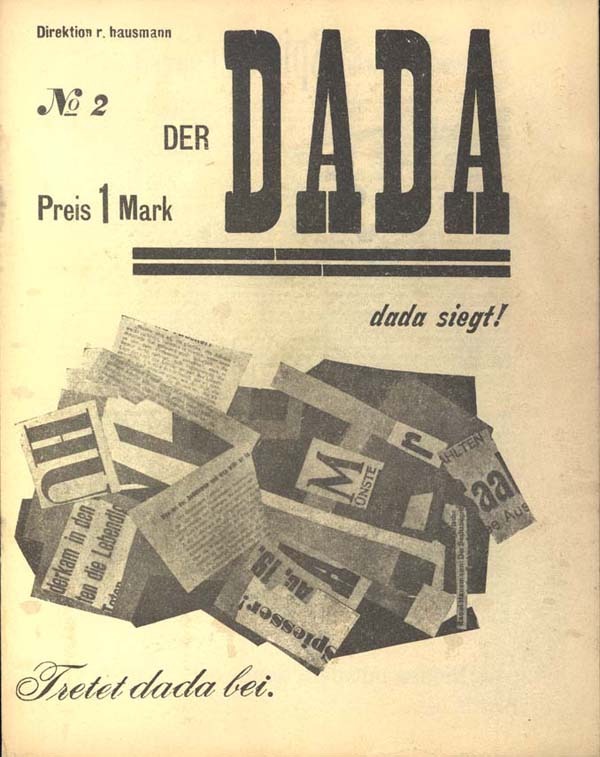

Raoul Hausmann: Dada siegt! |

|

Raoul Hausmann: Tête mécanique 1919-1920. |

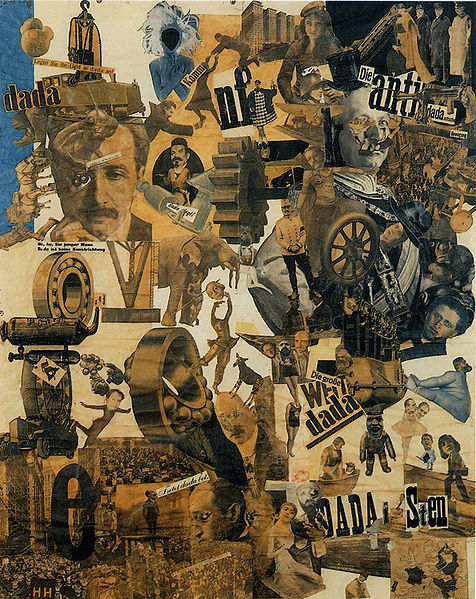

Raoul Hausmann was born in Vienna (1886). He spent his early years in Berlin where he met with Johannes Baader and who joined him and Richard Huelsenbeck in founding Dada Club in 1918. During this period of intense activity he contributed to the review Die Freie Strasse and to the Club Dada. He founded and ran, together with Joannes Baader and Richard Huelsenbeck Der Dada and organized the first Dada exhibition in Berlin.

Die Freie Strasse

Nr. 9. November 1918. "Gegen den Besitz!" [Editors: Raoul Hausmann and Johannes Baader.] (4) pp. Front page with massive block, tilted on the diagonal, printed in black. Tabloid folio, folded as issued. Texts by Raoul Hausmann ("Gegen den Besitz!," uncredited), Johannes Baader ("Die Geschichte des Weltkrieges," under the pseudonym Joh. K. Gottlob), Karl Radek ("Revolution und Konterrevolution"), et al. "That psychoanalytic ideas were acceptable to Dadaists in Berlin was consistent with their adherence to systematic politics, which Dadaists in France, Switzerland and America rejected. Even so it was not Freudian psychoanalysis that interested Dada in Berlin, but a psychotypology that was based on the researches of Otto Gross as systematized in 1916 by Franz Jung... who, the following year, founded the review Die Freie Strasse to propagate these views. It became the first voice of Dada in Berlin" (Rubin).

Berlin-Friedenau (Verlag Freie Strasse), 1918.

After the Dada movement, he undertook research in optophonetics, and at the beginning of the 1930s, photography became his preferred means of expression, with views of the Baltic Sea, the island of Sylt, and numerous nudes on the beach (Vera Broido). In 1933 he took refuge in Ibiza. There he developed research, not so far from that of ethnography, on the traditional settlement. From 1937-38, he lived in Czechoslovakia, where he began more research on photography. During the war he lived in a little village in France, near Limoges. After the war he moved to Limoges and, thanks to a parcel of photographic paper sent by Moholoy-Nagy, he made his first photograms. Then he returned to work in photography, photomontage, and sound poetry. From 1959 to 1964 painting became one of the most important aspects of his artistic production, which he later transformed into pictographic writing. Hausmann died in Limoges in 1971.

Richter and Huelsenbeck were responsible for bringing the Dada virus to Berlin where it found a highly favourable culture medium in the little libertarian group formed by Raoul Hausmann, Franz Jung, Johannes Baader, George Grosz, John Heartfield and a dozen young intellectuals more or less recently graduated from Herwarth Walden's Sturm.

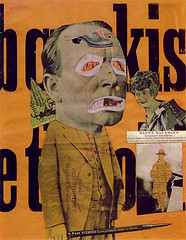

Raoul Hausmann: The Art Critic (Der Kunstkritiker - 1919-20). See the article by Michael Glover "Great Works: The Art Critic 1919-20 (31.8x25.4 cms)" in The Independent.

Hausmann, a founding member of the Berlin Dada group, developed photomontage as a tool of satire and political protest. Although the 'art critic' is identified by a stamp as George Grosz, another member of the group, the image was probably an anonymous figure cut from a magazine. The fragment of a German banknote behind the critic's neck suggests that he is controlled by capitalist forces. The words in the background are part of a poem poster made by Hausmann to be pasted on the walls of Berlin.

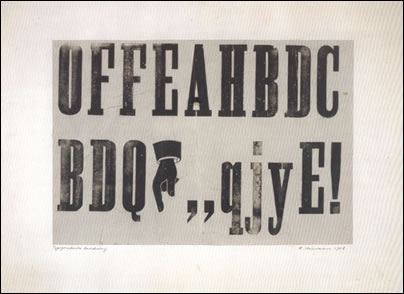

Raoul Hausmann: Phonetic poem - 1918

Raoul Hausmann: Dada Cino - 1920

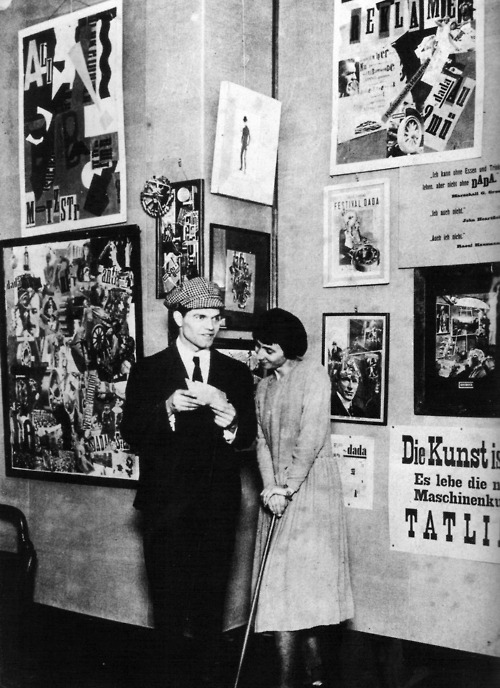

Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch at the opening of the First International Dada Fair held at the Otto Burchard Gallery, Berlin, June 30, 1920.

Photo by Robert Sennecke

Raoul Hausmann: Elasticum, 1920, collage and gouache

Courtesy of the Galerie Berinson, Berlin

See Cut & Paste, a history of photomontage for articles and illustrations about Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, John Heartfield and Kurt Schwitters.

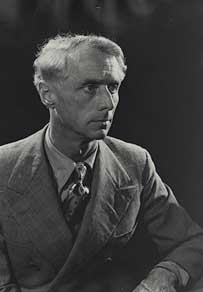

Richard Huelsenbeck 1892 - 1974

From the First German Dada Manifesto of 1918:

"Art in its execution and direction is dependent on the time in which it lives, and artists are creatures of their epoch. The highest art will be that which in its conscious content presents the thousandfold problems of the day, the art which has been visibly shattered by the explosions of last week... The best and most extraordinary artists will be those who every hour snatch the tatters of their bodies out of the frenzied cataract of life, who, with bleeding hands and hearts, hold fast to the intelligence of their time."

Poems by Richard Huelsenbeck in English translation by Johannes Beilharz:

http://www.jbeilharz.de/huelsenbeck/rh_poems.html

These poems were first published in the volume Phantastische Gebete (Fantastic Prayers) in 1916 (Collection Dada, Zurich), then reissued in 1920 in an expanded edition with illustrations by George Grosz by Malik Verlag, Berlin.

The translation is based on the text of the 1960 edition published by Arche Verlag, Zurich with a new dedication and preface by Richard Huelsenbeck.

Sascha BRU - "Schliesslich ... Don't forget. Richard Huelsenbeck, Cultural Memory, and the Genericity of (Dada) Historiography "

Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire - Année 2005, Volume 83, Numéro 83-4, pp. 1319-1331

An interesting article on Huelsenbeck in full text.

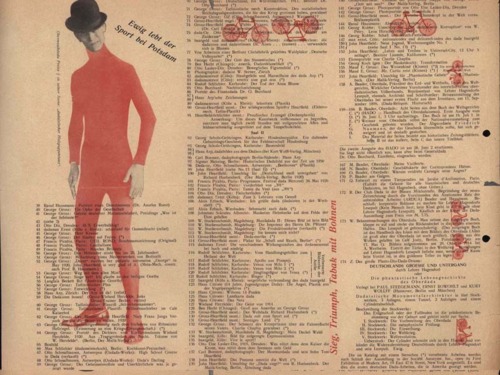

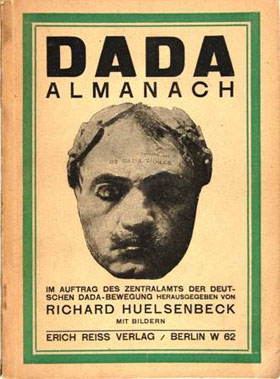

Issued in the autumn of 1920, just after the close of the Erste Internationale Dada Messe, the Dada Almanach was the first attempt to give an account of the movement's international activities, at least in Europe. Published on the initiative of Huelsenbeck, who was absent from the exhibition,...it contained important articles on the theory of Dadaism... valuable statements by the Dada Club and some pages by some less well-known Dadaists, such as Walter Mehring ("You banana-eaters and kayak people!"), sound and letter poems by Adon Lacroix, Man Ray's companion in New York, not to mention a highly ironical letter by the Dutch Dadaist Paul Citroën, dissuading his Dadaist partners from going to Holland. The volume was also distinguished by the

French participation of Picabia, Ribemont-Dessaignes and Soupault, quite unexpected in Berlin; their contributions were presumably collected and sent on from Paris by Tristan Tzara. The latter, living in Paris with the Picabias since early January 1920, gave in the Dada Almanach a scrupulous and electrifying account of the doings and publications of the Zürich Dadaists.... one of the most dizzying documents in the history of the movement.

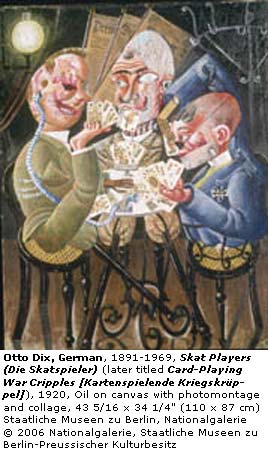

Otto Dix 1891 - 1969

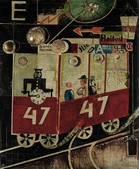

The Electric Tram

Biography on The Online Otto Dix Project

The 1919 oil-and-collage-on-board work The Electric Tram by Otto Dix was one of few lots to sell far above its estimate at a Sotheby's auction in February 2012. Valued at 700,000 pounds to 1 million pounds, this Dada-influenced evocation of urban life was also making its debut at auction, this time from a German collection. It was bought by a telephone buyer for 3 million pounds.

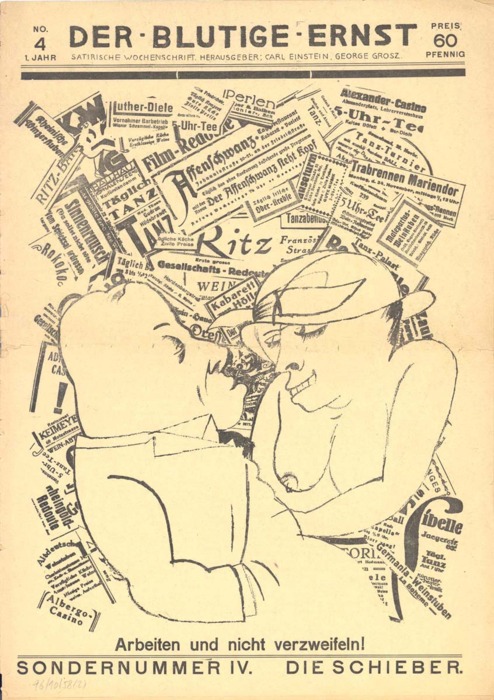

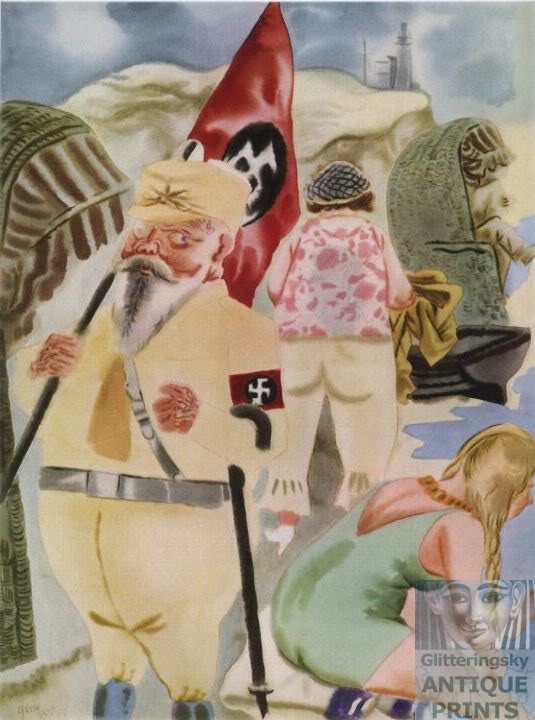

George Grosz 1893 - 1959

George Grosz biography on WikiArtis

George Grosz: Man of Opinion

George Grosz: Monteur John Heartfield (1920)

George Grosz: Der Blutige Ernst

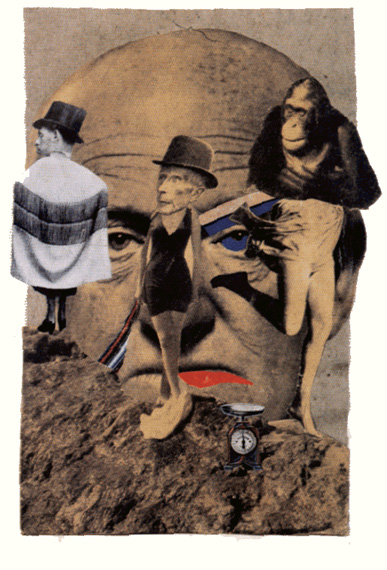

John Heartfield 1891 - 1968

John Heartfield 1891 - 1968

John Heartfield biography on WikiArtis

In 1918, Heartfield made a decision that would ultimately impact the rest of his career. He became a member of the Berlin Club Dada as a protest to Germany's current barbaric state and also joined the German Communist Party.

In 1919, after co-editing Jedermann sein eigner Fussball that was banned after its first edition, Heartfield joined his brother Wieland and George Grosz to found Die Pleite, a satirical, political magazine.

Continuing his activity in the Dada club, in 1920, he helped organize the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe (First International Dada Fair) in Berlin.

Jedermann sein eigner Fussball - February 1919

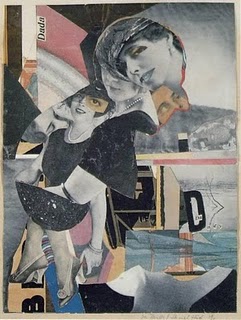

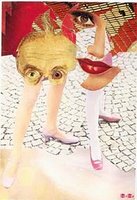

Hannah Höch 1889 - 1978

Hannah Hoch: Social Conscience and Political Commentator of Unmediated Expression

Hannah Höch was a pioneer Dadaist of 1920's Berlin. Somewhat forgotten, or at least pigeon-holed by art history; a social provocateur who clashed with the Nazis and was found guilty of Entartete Kunst (degenerate art).

The exhibition is a survey of the artist's works on paper and is the first major exhibition of Höch's art in Great Britain, bringing together over 100 works from major international collections. The exhibition examines Höch's career from the 1910's to the 1970's – if circumnavigating her prolific array of oil painting and drawing – the exhibition at least focuses on her most remembered output – photo-montage and collage – and her works of 'fantastische kunst'.

Höch's art was often an astute social satire on the female form, and the politics of Europe. The artist's human condition is resolutely female, and reflects her own experiences. A reflection of the female form and identity in society, as well as art.

These were figurative abstractions of tension and urgency. A juxtaposition of formal abstract aesthetics and emotional socio-cultural clout - initially reflecting a period of enthusiasm and great change in a post First World War Berlin.

Yet Höch's art was radical in contrast to the purely formal concerns of the Dadaist movement. The 'simultaneous muddle of noises' that the Dada Manifesto called for was discarded by Höch for a certain aesthetic balance, a definite composition, and a narrative structure, often politicised.

This one-woman Dadaist revolution also reflected a more obvious socio-political content and feminist drive, prevalent in the creative party of 1920's Berlin, eventually to be trampled under booted heel by a 'mad, inhuman, bestial clique' – as the artist herself described the Nazis – once she was no longer muted by their tyranny.

In fact the Second World War saw the artist publicly derided for her degenerate works and she lived out the war in cautious seclusion. A period that saw no public displays of her work, or opinion. Yet her art was spared exhibition in Die Ausstellung Entartete Kunst - the Degenerate Art exhibition of 1937 - as many of her peers fled Europe to America to continue the movement.

But it was the compositional harmony of Höch's work as opposed to the 'anti-art' of the Dada aesthetic that may have been the reason for her seeming erasure from Dadaist history. It was in the 1920's that fellow Dadaists John Heartfield, and George Grosz decried her inclusion in the First International Dada Fair. more

Paul Black in Artlyst - February 4, 2014

Hannah Hoch: The woman that art history forgot

Hannah Hoch has been overshadowed by her male counterparts and all but forgotten, but she helped to change the course of art.

Looking back on that great early 20th century upsurge which turned art upside down, it's all men, men, men. Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism and all the other great world-changing isms were about testosterone-fuelled mega-egos buffeting each other in the creation of mind-bending imagery and belligerent manifestos. There were, of course, plenty of women around in Paris, Berlin and the other great centres, but they tend — even if they were artists themselves — to be seen as appendages to better-known men; as muses, models and tea-makers rather than as contributors to the greatest artistic revolution the world has even seen. [...]

A pioneer of photomontage, whose images of women presaged the ideas of Simone de Beauvoir and Second Wave Feminism half a century later, Hoch was a pivotal figure in Dada, the anti-art movement that outraged conventional opinion in the final years of World War One, working alongside iconic male artists such as George Grosz, John Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann. Or was she?

Hoch isn't even mentioned in the history of Dada in Berlin, written by its notional founder Richard Hulsenbeck. Numerous major exhibitions and studies of Dada have failed to include any of her works. You'd be forgiven for thinking Hoch had been dropped into the story retrospectively, an enthusiastic hanger-on perhaps, promoted from the crowd to conform to our current ideas of how history should have been. The one Dadaist who did include Hoch in his memoirs, Hans Richter, recalled her contribution as the "sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money." [...]

Mark Hudson The Telegraph 14 Jan 2014

Hannah Hoch and the Dada Montage - Before Digital

Hannah Hoch (born Anna Therese Johanne Hoch on November 1, 1899) remains a well-known member of the Berlin Dada movement, and was among the first prominent artists to work with photo-montage techniques. Hoch attended the College of Arts and Crafts in Berlin from 1912 to 1914, during the tense lead-up to the first World War.

Hoch later described the war as having shattered her view of the world and affording her a newly political consciousness. Hoch initially became involved with Dada around 1919, as a result of her relationship with fellow Dadaist Raoul Hausmann. It was through Hausmann that Hoch was introduced to several other influential artists of the Dada movement, among them Kurt Schwitters, Hans Richter, and Piet Mondrian. Hoch's work, while mostly in keeping with the general Dadaist aesthetic, skillfully added a wryly feminist note to the movement's philosophy of disgust with the perceived wrongs of society.

The Dadaists insisted that the valuing of "logic" among modern cultures had led to an over-valuing of conformity, classism, and nationalism which in turn provided a suitable environment for the horrors of World War I. Dadaists therefore rejected this devotion to reason in favor of chaos, nonsense, and irrationality. Through her art, Hoch quietly submitted female equality to the list of anti-bourgeois and radically leftist sentiments which Dada espoused.

Unfortunately Hoch remained alone in her attempts to convey this message, and remained the only female Berlin Dadaist, never fully accepted by the rest of the group. Hans Richter patronizingly dismissed her contribution to the movement by calling it merely "the sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money," failing to note that Hoch was among the few members of her immediate artistic circle with a reliable income. She herself wrote:

"None of these men were satisfied with just an ordinary woman. But neither were they included to abandon the (conventional) male/masculine morality toward the woman. Enlightened by Freud, in protest against the older generation... they all desired this "New Woman" and her groundbreaking will to freedom. But—they more or less brutally rejected the notion that they, too, had to adopt new attitudes...This led to these truly Strinbergian dramas that typified the private lives of these men." more

by Meghan Maloney - April 29, 2013

Anna Therese Johanne Höch was born in Gotha, Germany, in 1889. She studied graphic arts at the College of Arts and Crafts in Berlin from 1912 to 1914 until she was recruited to work for the Red Cross during the war. Höch also trained in fabric design and textiles after her time spent in the war, working part time for Ullstein Verlag, Weimar Berlin's largest publishing empire. She created lace tablecloths and needlepoint patterning and most notably had access to the company's catalogues which she used to create her early photomontages. In 1915, Höch met Raoul Hausmann and through him became associated with the Berlin Dadaists. Hausmann and Höch, under the influence of Dadaism, perfected the art of photomontage and used it as satirical propaganda. Höch became the only female to show works at the First International Dada Fair in 1920.

In 1922, Höch ended her relationship with Hausmann and left the Berlin Dadaists. Known for her independent spirit, masculine dress, and bisexual tendencies, Höch then had a relationship with Til Brugman, the Dutch writer and linguist from 1926 to 1929. She continued to produce her own art and champion female rights until the onset of World War II when the Nazi regime banned all artistic movements, claiming them to be "degenerate." Instead of fleeing Berlin, Höch chose inner exile so she could protect her precious artwork and Dada memorabilia. After the war, Höch quietly remained in Berlin and focused on smaller works. She died in 1978 at the age of eighty-nine. The Museum of Modern Art in New York held a retrospective of her work in 1997 to commemorate her contribution to Dada and women's art as a whole. NMWA's collection includes eighteen objects created by Höch.

by Ali Printz

Currently an intern in the Library and Research Center at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Hannah Höch: Cut With the Kitchen Knife

Hannah Hoch: Dada Artist Or?

Have you ever felt out of place? Like you didn't belong? Do you think art sometimes doesn't make sense? Welcome to Dada art in the 20th century.

In the fever of WWI, a group of artists banded together and began to create work that questioned the limits of art and of humanity. Their emphasis was on chance, accidents, the insane, the absurd responding to the horrors of the war. Hannah Hoch's photo collage Cut With the Kitchen Knife is a perfect example of the chaos the Dadaists attempted to illustrate. Photo collage or photo montage works so well here in its strange skewing of reality. Hoch takes images from newspapers and combines them in irreverent and nonsensical ways,– distorting what is real and what is imaginary. It is actually a quite cutting example of the power of propaganda as well –as often the newspapers were (or some would argue are still). It is as if Hoch jumbles around the news to give us a more "true" version of reality –or at least what her reality felt like during her historic moment.

Dada was not a catalyst in inspiring Hoch's work. She had a love of design and absurd disjunction. Hoch is not considered a contemporary artist. Many artists are stuck in historical brackets that limit our appreciation of their life's work, and Hoch is very much stuck.

Molly McQuillen in Burchfield Penney Art Center at SUNY Buffalo State - December 16, 2014

Hannah Höch: DaDa Dolls - 1916

Hannah Höch: DaDandy - 1919

Hannah Höch: And When You Think the Moon is Setting - 1921

The Quiet Girl with a Big Voice - Hannah Hoch

Cologne

Soon after the declaration of war, as Arp was taking refuge in Switzerland, Max Ernst went into combat in the German artillery. Discharged in the beginning of 1919, he returned to his native Westphalia, where Arp was to join him a few months later, fortified by his Dadaist experience in Zurich.

Meanwhile, in Cologne, Ernst had met Alfred Grünwald, son of a corporate managing director, founder of the Rhine branch of the Communist Party, and with a reputation under the pseudonym Johannes Theodor Baargeld, as a poet and painter.

Like the Berlin Dadaists, the two men took part in the revolutionary movement of 1918-1919. They published a Communist periodical, Der Ventilator (impossible to find today, but recently reprinted), some issues of which sold up to twenty thousand copies on the street and at factory and barrack gates, and which would ultimately be banned by the occupying British forces in 1919. [...]

Thanks to the shared intellectual resources of Ernst, Arp and Baargeld, Dada was to see some of its finest accomplishments in Cologne in collage. [...]

But of all the experiments tried out in Cologne, the one that remains, historically, the most important was the fusion of these distinct talents into a series of anonymous works facetiously named Fatagaga ("Fabrication of tableaux guaranteed to be gasometric"). By creating in this way a company producing collective collages made with or without prior agreement, the three men inaugurated a technique that the surrealists would fruitfully develop (as the "exquisite corpse"). This company was called Centrale W/3 ("W für Weststupidien, 3 für die 3 Verschworenen (conspirators): Hans Arp, J. T. Baargeld und M.[ax] E.[rnst]"); its mouthpiece was the eponymous magazine Dada W/3, which also did not survive its infancy.

Excerpt from Michel SANOUILLET, Dada in Paris.

Willy Fick 1893 - 1967

Anti-war proponents such as Willy Fick, his sister Angelika and his future brother-in-law Heinrich Hoerle felt confident the S.P.D.(Social Democratic Party), would not vote for war credits in 1914, but, when it did Willy Fick registered as a conscientious objector. He served in a non-combat position as a wagon driver from 1917 to 1918. He had time until 1917 to develop his art which started with anti-war linocuts mocking the sheepishness of the masses. Willy's acquaintanceship circle enlarged during the war to include Otto Freundlich and Carl Oskar Jathoboth of whom had returned early from the front. From 1916 onwards Carl and Kaethe Jatho ran an artist-centered anti-war group in their home where Willy met their friend Franz Wilhelm Seiwert an artist and arts theorist with a broad circle of friends. Everyone was connected either through art, politics, war or love. Willy got into closer contact with the married artists Marta Hegemann and Anton Raederscheidt who were friends of the Hoerles.

However unlike those noted, Willy Fick had full-time employment. He worked for the City of Cologne Transportation Department between 1918 and 1923 during a time when cash-strapped Germany fomented with revolt. Since Willy squeezed his art time out from work and because he was a natural buffoon, Fick became the butt of sarcastic humour during the Dada time. He appeared in the Bulletin D exhibition as an "Unknown Master from the Beginning of the 20th Century" and in the Brauhaus Winter exhibition as "a vulgar dilettante". In a taped interview with Prof. Michel Sanouillet in 1967 he explained his part in these exhibition/events that mocked the established art world. He also stated that his work traveled with the Bulletin D exhibition to the Graphic Cabinet Von Bergh and Co in Duesseldorf in 1920. Fick's first works under his own name appeared in Stupid 1, the catalogue of the continuous exhibitions at the Raederscheidt apartment on Hildeboldplatz. His child-like works were in keeping with the Stupid group's intention to create a newer better world after the Armageddon of WWI. Fairy-tale like watercolours from this period show the hope for a better world that was soon dashed by the dire post-WWI situation and by the death of his sister Angelika Hoerle who died of tuberculosis at 23 years of age. [...]

By Angie Littlefield from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

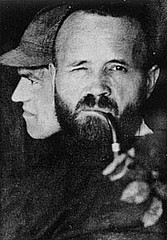

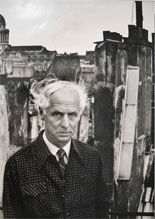

Max Ernst 1891 - 1976

Max Ernst by Man Ray

Max Ernst biography on WikiArtis

LONDON.- The Impressionist and Modern Art and The Art of the Surreal Evening Auctions will take place on 7 February 2012 at 7pm with a pre-sale estimate of £86,205,000 -127,090,000 (corresponding estimate in 2011: £73.8-109 million). Combined with the Impressionist, Modern and Surrealist works which will be offered in Living with Art – A Private European Collection, the total value of art offered in the Evening Sales between 7 and 9 February is £97,761,000-145,090,000.

Overall the sale offers 10 works by Max Ernst, an artist for whose work the market has recently shown a powerful hunger. Christie's achieved two new consecutive record prices for the artist at auction in 2011, in London and New York, culminating last November when The Stolen Mirror, 1941, sold for $16,322,500 (£10,283,175).

Max Ernst

Max Ernst

Max Ernst: Oedipus Rex 1922

Johannes Theodor Baargeld 1892 - 1927

(Alfred Emanuel Ferdinand Grünwald)

Biography and some works of 1920 in The Museum of Modern Art

Hanover

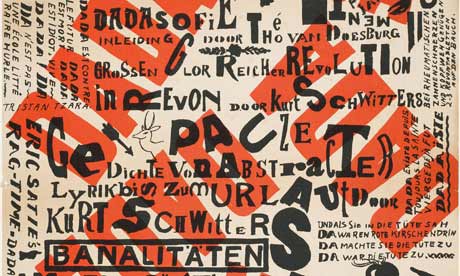

Kurt Schwitters 1887 - 1948

Holland

Theo van Doesburg (Christian Emil Marie Küpper)

1883 - 1931

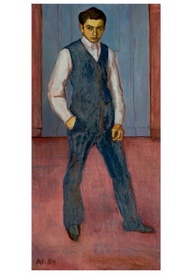

Theo van Doesburg in 1915

Biography at the MoMA

Biography on Wikipedia

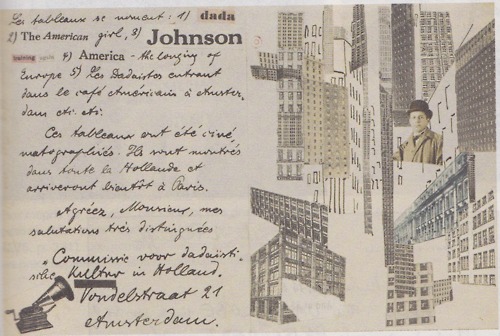

Poster of the Kleine Dadasoirée 1922

Paul Citroen 1896 - 1983

Paul Citroen - Self-portrait - 1914

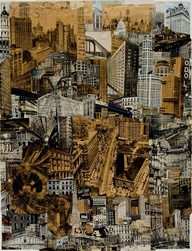

Paul Citroen - Metropolis - 1923

Paul Citroen was born in Berlin, December 15, 1896. Dutch photographer, photomontagist and painter, active also in Germany. He belonged to the DADA group in Berlin and was a friend of George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield and Erwin Blumenfeld. From 1922 to 1925 he was associated with the Bauhaus in Weimar, producing during this period the photocollage Metropolis (1923; Leiden, Rijksuniv.), the single work for which he remains best known, and which has become a classic image of the 20th century city. His period at the Bauhaus clearly helped shape his photographic style, his photomontages in particular betraying the influence of both Dada and Constructivism. In 1927 he moved to the Netherlands, founding and then teaching at the Nieuwe Kunstschool in Amsterdam (1933-7). From 1935 to 1940, and again from 1945 to 1960, he was professor of drawing and painting at the Academie voor Beeldenden Kunsten in The Hague. He continued to work as both a painter and photographer without ever recapturing the fame that he had enjoyed with his work of the 1920s. He died in Wassenaar, March 13, 1983.